When we reflect on the historic 1954 case, Brown v. Board of Education, and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s that worked to shift the educational landscape in this country, many liberals and progressives often view that era as a time filled with hope and promise. Looking back at pictures of young Ruby Bridges escorted by U.S. marshals entering a school where she was not wanted, many marvel at how brave she was, but seldom question the need for that bravery or the damage done to a young child’s psyche upon being subjected to, and enduring, prolonged violence and hatred. People — Black and white — often frame forced desegregation through the lens of white saviorism while ignoring the specific gifts of Black Southern schools of that period. Despite the “separate but equal” ruling established by the Plessy v. Ferguson case of 1896, which promoted separate but equal school facilities for Black and white students, the equity promise was not upheld as Black schools were not provided the same resources or funding as their white counterparts. Notwithstanding the limitations, before the push for integration, some argue that Black schools and Black teachers in the South were creating positive and psychologically safe learning environments for Black children, and had those schools been properly resourced, maintaining separation may have been a better option for those Black and vulnerable children (Diette et al., 2021).

It is essential not to view the Civil Rights era solely through an optimistic lens, while overlooking the seismic shift that forced integration caused and failing to recognize the many ways in which those systemic changes may not have achieved what they set out to do. Years after the “separate” but “equal” doctrine, in 1935, W. E. B. Du Bois asked the question: “Are these separate schools and institutions needed? And the answer, to my mind, is perfectly clear. They are needed just so far as they are necessary for the proper education of the Negro race” (p. 328).

Dubois also stated:

…if we recognize the present attitude of white America towards black America then the Negro not only needs the vast majority of these schools, but it is a grave question if, in the near future, he will not need more such schools, both to take care of his natural increase, and to defend him against the growing animosity of the whites. (Dubois, 1935, p. 328)

Christanto further upheld Du Bois’ assertion when recounting a study on the effects of integration:

A 1968 study revealed that the mental health of Black students has shown marked trends before and after desegregation legislation, with reports indicating increased anxiety, lower self-esteem, and higher rates of depression as Black students entered integrated schools [7]. Moreover, while one might expect conditions to improve over time, data from the 1990s revealed a troubling 73% increase in suicide rates among Black students. (n.d.)

So, given the climate before and during the Civil Rights era, when folks think about desegregation and Ruby Bridges, they must also consider how, in many ways, she was robbed of being a little girl because she was forced to be a symbol; her purpose was to inspire and change minds but imagine if integration were not just a legislative demand, but instead, it was achieved in a more compassionate and mutually respectful and beneficial way. What if there were people, Black, Brown, Asian, and white, who wanted their children to learn together and who supported each other’s differences? What if Ruby had been allowed to fully be a Black child proud of her history, not needing to assimilate or acquiesce to white American educational indoctrination? What if the Civil Rights Movement had offered more than just integration for the sake of integration, but instead considered the emotional needs of Ruby Bridges and others, like the Little Rock Nine, who were forced in 1957 to integrate Central High School in Arkansas (Bunch, n.d.)? Instead of trying to fit Ruby, a circle, into the mainstream public educational system, a square, what if she had been given the space to grow among people who wanted her there, who loved her, embraced her culture, who felt her history was U.S. history, and who not only prepared her to compete academically in U.S. American society and beyond but also taught her self-pride and the importance of advocating for her rights and the rights of other marginalized groups?What if she had been told that changing society was not a burden that only Black people needed to carry, but that the responsibility belonged to all people, particularly those who created the separation?

I know that for many readers, such a place does not exist, but for me, sadly, as of last month, a place that once did is no longer. Yes, you may hear many reasons for this decision, including financial mismanagement and shortsightedness, but to me, all of the reasons are secondary to the way Manhattan Country School (MCS) and its community have produced environmentally conscious, socially aware young racially and ethnically diverse people committed to advocating for themselves and those less fortunate. I want to share the story of Manhattan Country School with you because, despite current attempts at historical erasure and it being the end of an era for the school and its tight-knit community, it is a story that everyone should know. It is a story of what is possible when we choose to foster educational environments geared toward uplifting ALL children, rather than a select few.

In 1973, at the age of four, my parents enrolled me in a social experiment, one that I participated in for eight years. My classmates and I, a diverse group of Black, Brown, Jewish, white, and Asian children from varying socioeconomic backgrounds, were all actively engaged in this experiment. On the heels of the Civil Rights Movement, inspired by the teachings of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and John Lewis, among others, Gus and Marty Trowbridge, two young white educators, embarked on a journey to create a progressive, sliding-scale, integrated private school in New York City, and they succeeded. In 1966, moving into a townhouse, or mini-mansion by NYC standards, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, a neighborhood that bordered both a low-income neighborhood and one of the wealthiest in the city, Manhattan Country School became the first fully integrated private school in New York City (Archibold, 2002; “Manhattan Country,” n.d.). It is worth noting that there were no charter schools at this time.

Understanding that private school education in a city like New York was largely offered to children of white affluence, Gus and Marty embarked on a unique endeavor, one where they asked what would happen if they created a school environment consisting of students from diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds, what if they employed male and female Black, Brown, white, and Asian teachers so that students would feel racially represented, bought a farm where city kids could be exposed to all aspects of farm life and learn to build a deeper appreciation for the environment, and what if they offered a sliding scale tuition so that all groups, unhindered by financial constraint, could benefit from the knowledge each of these groups held?

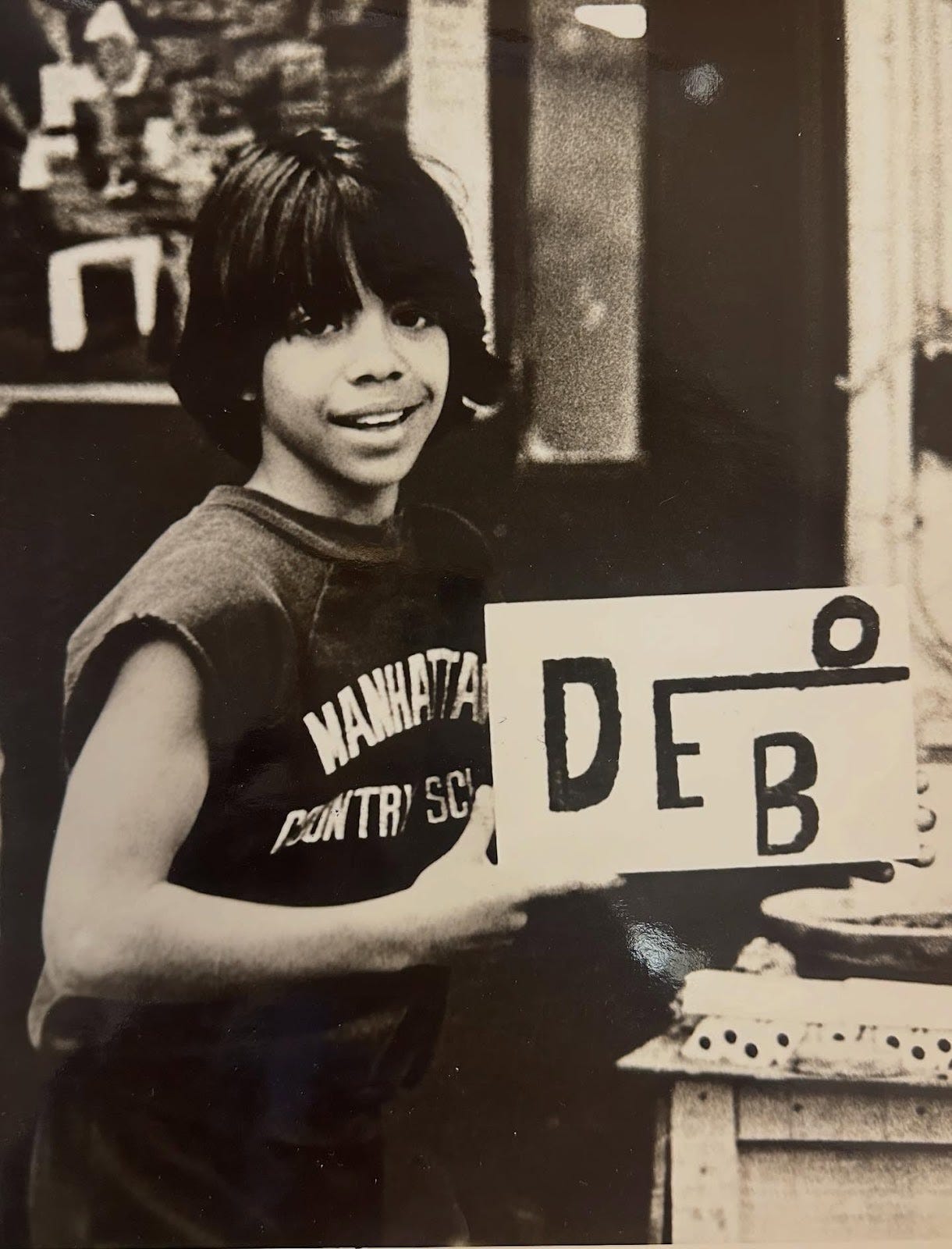

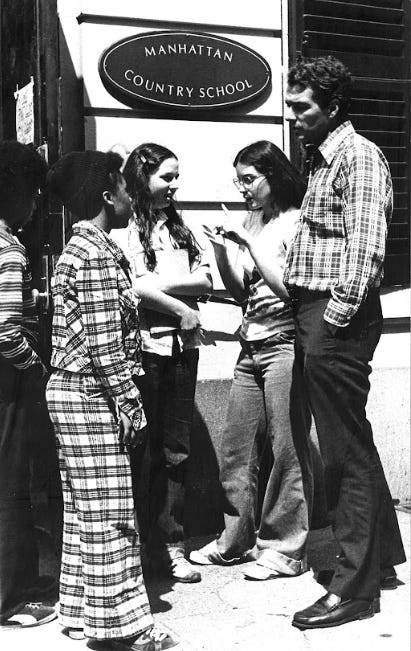

For almost 60 years, that was the mission of MCS. The social experiment the founders created was successful in doing what it set out to do, having shaped notable graduates such as Lee Gelernt, Deputy Director of the ACLU Immigrants’ Rights Project (his mother, Lois Gelernt, was my Kindergarten teacher and is pictured in this photo), former Obama appointee Debo Adegbile (young Debo pictured below), who served as the commissioner on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, or Akemi Kochiyama, scholar-activist, community builder, and granddaughter of the famous Japanese American Civil Rights activist, survivor of Japanese internment camps, and dear friend of Malcolm X, Yuri Kochiyama (ACLU, 2025; U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, n.d.; Black Feminist, n.d.; Zinn Education Project, 2025). As an MCS alum, I also chose a similar path, having tried throughout my life to amplify the experiences of Black and Brown people through my involvement in higher education, scholarly work, reproductive activism, mentoring young people of color, and within my profession.

MCS, despite the odds, successfully created several generations (many alums sent their offspring to the school) of insightful, thoughtful, social justice-minded individuals who took what they learned, carried, and applied the core tenets of the organization in every aspect of their lives. As MCS puts it:

“As a community, we are deeply committed to upholding a shared social responsibility to create a more just world. Our proud legacy lives on through our graduates, who bring curiosity and critical analysis to every new situation. With the confidence and skills to actively shape a better world, they don’t simply study it — they transform it. At our institution, social justice is both a study and a practice, blending theory with practical application grounded in the social sciences. We focus on understanding our social world and empowering our students to become agents of change.” (n.d., para. 1)

Sadly, despite numerous Zoom roundtables, meetings, and community efforts to keep the school open, Manhattan Country School was recently forced to close its doors, marking the end of this powerful social experiment. Many alums and community members (many of whom have been engaged with MCS since its inception), as well as I, are now left with a deep chasm in our hearts. Words cannot express the sadness that many of us feel as a result of its closing.

“Manhattan Country School was born in an idealistic time by idealist teachers and parents. As a student there, I marched against the war in Vietnam, visiting churches and synagogues, studied Abraham Lincoln and Harriet Tubman, learned to milk cows and make jam, made friends who lived on Fifth Avenue and friends who lived in the projects in Harlem, and visited Grant’s Tomb and Jackie Robinson’s funeral (on the same day). To me, its demise is a symbol of this era in which greed, cynicism, and self-centeredness have taken hold of America.”

— Bill Wolfsthal, Class of 1976 (grades 1–5)

“I grew up in the segregated South and became a member of the Civil Rights Movement during my teenage years. In those days, I was arrested and put into jail for my and my fellow students’ demonstrations against the system. At that time, I told myself I was protesting so that my future children could have a life that opened doors to greater equality than mine did. A large part of my dream in those days was for my children to experience an integrated education comparable to and alongside the education white children were receiving. And I wanted my children to be accepted for who they were. When my husband and I toured MCS, we were impressed by the fact that not only was the student body fully integrated (rather than having an occasional lone black child in a classroom), but unlike other private schools we had toured, the teaching staff was fully integrated too.”

-Nell Braxton Gibson, Parent of two MCS alums, Civil Rights activist, and author of the book Too Proud to Bend: Journey of a Civil Rights Foot Soldier

“I believe that MCS deeply influenced who I am. As a bi-racial woman (my mom is Black, descended from the enslaved, and my dad is Jewish, and his parents immigrated to the U.S. from Eastern Europe. MCS gave me a place where I felt safe and could develop my identity with love and support. That was a gift.”

- Robin Levi, Class of 1982, Retired women’s human rights lawyer

“MCS was, for me, a foundation of ethics, community, and learning that I would never have had access to anywhere else in NYC or the world. It was where I learned to dye wool, milk cows, tap trees, and learn grammar. We ate arroz con pollo on Monday and Sloppy Joe’s on Friday. Amazing.”

-Raymi Taylor, Class of 1984, Owner of Reimi Botanicals, an environmentally conscious beauty brand

Everything must die, I suppose, but let us not forget that a place such as this existed, that a learning environment was successful in testing the boundaries of the traditional American public and private school system, that the school built socially and environmentally conscious, responsible leaders who not only worked, and continue to work, to advance society, not in a performative, color evasive, forced way, but instead deliberately and consciously acting upon the belief that it is possible for students of all colors and varying socioeconomic backgrounds to learn together and from one another. The school emerged from the assumption that mutually beneficial integration was possible. Students could thrive academically not by sheltering them from this country’s painful history, but by teaching an appreciation for diverse historical narratives and literary forms, promoting advocacy, valuing a rigorous and robust academic curriculum, encouraging musical and artistic expression, and emphasizing the importance of environmental stewardship.

In 1973, I enrolled in this MCS experiment, and it forever changed my life and the lives of all those who participated. Manhattan Country School was not just another elite New York City private school; it was born out of community, and the people who held it together over the years were dedicated to its mission. Manhattan Country School represented the best that integration had to offer and should serve as the rule, not the exception, when we consider modern education.

MCS, thank you for shaping the person I am today. For me, as an educator, you will forever serve as a beacon of what is possible when we think about fostering positive, affirmative, culturally responsive educational outcomes for children of all races. Through your work and commitment to your students, you have shown that each of us — when we move with intention, authenticity, and dare to imagine things differently — can be a force of good in this world. You will be missed, but rest assured, those of us who loved you, who learned within your walls from the exceptional teachers, and who poured time, money, and effort into building and uplifting this community, we will not allow you to be forgotten.

Your promise lives within all of us, and we take you with us wherever we go.

Author’s Note: The author has made the purposeful decision in this work to capitalize “Black” and the names of other racial groups while leaving “white” lowercase. This is a grammatical decision made by the author and other Black scholars who work to decenter whiteness in scholarly work by choosing instead to center the experiences of Black people and others who have been historically overlooked (Appiah, 2020).

Special thanks to Mary Trowbridge, the daughter of Gus and Marty, for her assistance with the archived photos.

References

ACLU. (n.d.). Lee Gelernt: Bio. ACLU. https://www.aclu.org/bio/lee-gelernt

Appiah, K. A. (2020). The case for capitalizing the B in Black. The Atlantic, 18. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/time-to-capitalize-blackand-white/613159/

Archibold, R. C. (2002). A IS FOR AFFIRMATIVE ACTION; A minority of none. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/14/education/a-is-for-affirmative-action-a-minority-of-none.html

Black Feminist Taught Me. (n.d.). Akemi Kochiyama. Black Feminist Taught Me. https://www.blackfeministstaughtme.com/new-york-city/akemi-kochiyama

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Bunch, L. (n.d). The Little Rock Nine. Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine

Christanto, A. (2025, January 31). Brown v. Board of Education’s impact on the

academic achievement and psychological state of Black Students: Wrong Approaches and the creation of latent stereotypes in society. Columbia Black Pre-Law Journal. https://blackprelaw.studentgroups.columbia.edu/news/brown-v-board-educations-impact-academic-achievement-and-psychological-state-black-students

Diette, T. M., Hamilton, D., Goldsmith, A. H., & Darity, W. A. (2021). Does the Negro Need Separate Schools? A Retrospective Analysis of the Racial Composition of Schools and Black Adult Academic and Economic Success. RSF: Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 7(1), 166–186. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2021.7.1.10

Du Bois, W.E.B.(1935). Does the Negro need Separate Schools? The Journal of Negro Education, 4(3), 328–335. https://doi.org/10.2307/2291871

Manhattan Country School. (n.d.) Our founder’s story. Manhattan Country School. https://www.manhattancountryschool.org/social-justice-social-science

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. (n.d.). Debo P. Adegbile. U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. https://www.usccr.gov/about/debo-adegbile

Zinn Education Project. (2025). Yuri Kochiyama Biography. Zinn Education Project. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/yuri-kochiyama-was-born/